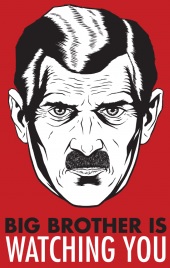

«1984» es uno de los libros más famosos de la historia. El año 1984 llegó y se fue, pero la visión profética y de pesadilla que George Orwell proyecta desde 1949 en este libro sobre el mundo amenazadoramente cambiante que se estaba avecinando, resulta más actual que nunca en este siglo que proclama con notable fanatismo el "cambio" y "más cambios" en busca de una utópica panacea.

«1984» sigue siendo el gran clásico moderno de la "utopía negativa", esa ahora llamada "cancel culture" o cultura  de la cancelación que define el fenómeno cada vez más extendido de retirar el apoyo moral y financiero, o incluso digital y social, a personas u organizaciones que los grandes centros de poder financiero o político consideran inadmisibles o "deplorables". Aunque esta novela sorprendentemente original e inquietante crea un mundo imaginario, resulta profética y completamente convincente desde la primera oración hasta las últimas cuatro palabras expresando su amor “al Big Brother” o "al Gran Hermano" (¿el líder "indiscutible" de hoy?) que “vela” por el "bienestar" y “vigila” para que haya “orden”. No puede negarse el poder de la novela sobre la imaginación de generaciones enteras, o el poder de sus amonestaciones; un poder que parece crecer, no disminuir, con el paso del tiempo y dibujarse con grandes rasgos en la realidad actual.

de la cancelación que define el fenómeno cada vez más extendido de retirar el apoyo moral y financiero, o incluso digital y social, a personas u organizaciones que los grandes centros de poder financiero o político consideran inadmisibles o "deplorables". Aunque esta novela sorprendentemente original e inquietante crea un mundo imaginario, resulta profética y completamente convincente desde la primera oración hasta las últimas cuatro palabras expresando su amor “al Big Brother” o "al Gran Hermano" (¿el líder "indiscutible" de hoy?) que “vela” por el "bienestar" y “vigila” para que haya “orden”. No puede negarse el poder de la novela sobre la imaginación de generaciones enteras, o el poder de sus amonestaciones; un poder que parece crecer, no disminuir, con el paso del tiempo y dibujarse con grandes rasgos en la realidad actual.

En la novela, los personajes se sienten acorralados en todos sus ambientes, rodeados de cámaras que los observan y micrófonos que los escuchan hasta en los lugares más privados (¿diríamos hoy que se haga por motivos de "seguridad nacional"?). Prácticamente todo lo que se dice, lo que se hace y hasta lo que se desea hacer y cuáles son los gustos y preferencias de cada uno está registrado y sirve para controlarlos. Encontramos en sus páginas que hay incluso expertos que te observan, te escuchan y examinan tus preferencias, los que, a su vez, perfeccionan constantemente su capacidad de leer las expresiones faciales de la gente (¿los actuales expertos en "face recognition" mediante programas cibernéticos?).

Si todo esto nos parece exagerado, miremos a la China de hoy: hay cámaras en todas partes vigilando a sus ciudadanos y todo lo que hacen en Internet está monitoreado. Se ejecutan algoritmos y se están realizando experimentos para asignar a cada individuo una puntuación social. Si no actúa o no piensa de la manera "políticamente correcta", le suceden cosas lamentables: pierde la capacidad de viajar, por ejemplo, o pierde su trabajo, o puede perder la libertad o hasta la vida. Sin duda, es un sistema sumamente abarcador y eficaz.

- Hits: 3821

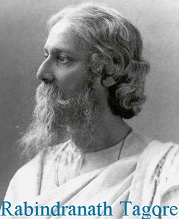

En la India, Rabindranath Tagore fue un gran poeta y Premio Nobel de Literatura en el año 1913. Durante su existencia destacó como un símbolo de libertad, humanismo y tolerancia. La Universidad que fundó en Bengala estuvo dedicada a los ideales de libertad. Su pensamiento se construyó influido por las grandes tradiciones de la India y por las ideas liberales europeas.

En la India, Rabindranath Tagore fue un gran poeta y Premio Nobel de Literatura en el año 1913. Durante su existencia destacó como un símbolo de libertad, humanismo y tolerancia. La Universidad que fundó en Bengala estuvo dedicada a los ideales de libertad. Su pensamiento se construyó influido por las grandes tradiciones de la India y por las ideas liberales europeas. que la violencia es el refugio final del Gobierno. Y, como no puede crearse ninguna energía sin resistencia, nuestra no-resistencia a la violencia del Gobierno debe ocasionar la paralización de éste”.

que la violencia es el refugio final del Gobierno. Y, como no puede crearse ninguna energía sin resistencia, nuestra no-resistencia a la violencia del Gobierno debe ocasionar la paralización de éste”.

I am too ignorant (entirely so, in fact) of how computer systems work and how they can be rigged, of polling and ballot procedures, and of how votes are counted and reported to the election authorities to have an informed opinion about whether the election this year was electorally stolen or not, though the proliferation of staggered vote dumps, and their frequently near-unanimous contents, certainly strike me as hugely suspicious. And while it is by now apparent that all the usual irregularities and frauds that have occurred in every previous democratic election in history, here and every other country in the world, did so again in this one, there is no means to prove that they were sufficiently numerous and widespread to have determined the final count that appears to have given Joe Biden the presidency. In that sense, then, the 2020 was not stolen—at least, it cannot be demonstrated to have been an act of highway robbery. But miscounting and misreporting votes is far from being the only way in which a democratic election can be stolen, as I believe this one was.

I am too ignorant (entirely so, in fact) of how computer systems work and how they can be rigged, of polling and ballot procedures, and of how votes are counted and reported to the election authorities to have an informed opinion about whether the election this year was electorally stolen or not, though the proliferation of staggered vote dumps, and their frequently near-unanimous contents, certainly strike me as hugely suspicious. And while it is by now apparent that all the usual irregularities and frauds that have occurred in every previous democratic election in history, here and every other country in the world, did so again in this one, there is no means to prove that they were sufficiently numerous and widespread to have determined the final count that appears to have given Joe Biden the presidency. In that sense, then, the 2020 was not stolen—at least, it cannot be demonstrated to have been an act of highway robbery. But miscounting and misreporting votes is far from being the only way in which a democratic election can be stolen, as I believe this one was. happened in 2020; numerous state and local governments, indeed, have boasted of having done just that from their concern for the mental, emotional, and physical welfare of the citizenry during the pandemic. By doing so, however, they ignored entirely the interests of the political candidates at every level of government, who went into the election season that began last year armed with strategies whose effectiveness depended upon the assurance that their campaigns would follow a fixed schedule allowing them exactly so many months, weeks, and days to build their case for election or reelection, and present it to the electorate before the voters went to the polls on the first Tuesday following the first Monday in November: a sure and regularized process that is not only of enormous benefit to the candidates, but also to the voting public itself. In 2020, state and local governments robbed both parties of that benefit by allowing voters to cast their votes before the incumbents had the time they deserved to fulfill the political commitments they had made during previous election cycles and finalize their political accomplishments, and that the electorate needed to judge for itself whether they had done so–or not.

happened in 2020; numerous state and local governments, indeed, have boasted of having done just that from their concern for the mental, emotional, and physical welfare of the citizenry during the pandemic. By doing so, however, they ignored entirely the interests of the political candidates at every level of government, who went into the election season that began last year armed with strategies whose effectiveness depended upon the assurance that their campaigns would follow a fixed schedule allowing them exactly so many months, weeks, and days to build their case for election or reelection, and present it to the electorate before the voters went to the polls on the first Tuesday following the first Monday in November: a sure and regularized process that is not only of enormous benefit to the candidates, but also to the voting public itself. In 2020, state and local governments robbed both parties of that benefit by allowing voters to cast their votes before the incumbents had the time they deserved to fulfill the political commitments they had made during previous election cycles and finalize their political accomplishments, and that the electorate needed to judge for itself whether they had done so–or not.  Juan Jacobo Rousseau.

Juan Jacobo Rousseau. También Juan Jacobo Rousseau escribió sobre la libertad. En su

También Juan Jacobo Rousseau escribió sobre la libertad. En su