People think me quite strange when I say that I love Tisha B’Av, the Jewish holiday which falls in the middle of summer when the days are long and the heat often unbearable. How could I love this holiday which is considered the saddest day of the Jewish year? Many people would opt to expunge this day from the holiday cycle altogether.

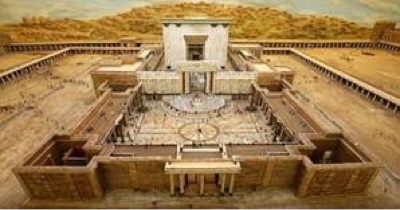

Tisha B’Av is a day of grieving, of destruction and loss—a mournful lament. Tisha b’Av, literally the 9th of the month of Av, commemorates the great catastrophe, the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple, the center of the world for the Jewish people. There were two Temples in Jerusalem—each supposedly destroyed on the 9th of Av—hundreds of years apart.

9th of the month of Av, commemorates the great catastrophe, the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple, the center of the world for the Jewish people. There were two Temples in Jerusalem—each supposedly destroyed on the 9th of Av—hundreds of years apart.

Many people imagine the ancient Temple as a magnificent stone building, set in a stone courtyard, set in a stone plaza, set in a city of stone; and they think of Tisha B’Av as a remembrance of the destruction of this stone city. Their vision of the Temple may not extend beyond the human confines, beyond the building complex. However, the Temple in Jerusalem has always been associated with the Garden of Eden, the garden of earthy delight. My own understanding of the Temple comes from the prophet Ezekiel. He was one of many who saw in the Temple a representation of Eden. In Ezekiel’s vision, a river flowed out from under the Temple and gigantic trees grew along the banks of the river, and wherever the river flowed, fish were bountiful and the plants flourished, freely giving their foods and medicines. What better description of Paradise? The Temple and the Garden were then one and the same. The Temple is an icon of the Garden, and the Garden is an icon of the Earth.

The text we read on Tisha B’Av, Eica (Lamentations) is a montage of devastating and gruesome images of the suffering that comes to an entire people when the Temple and the city of Jerusalem go up in flames. As poetry, the language of Lamentations invites our minds to roam and make associations. When I hear the word Temple, my mind jumps to the Garden of Eden and then to the Earth, and the suffering that the Earth and all of us are facing as we are caught in the whirlwinds of our changing climate.

On the evening of Tisha B’Av—as we gather together— the lights are turned off in the sanctuary. Each person takes a candle, lights it, and proceeds slowly and carefully to the bima—the platform where the Torah sits. We find a spot and lower ourselves to the ground—we humble ourselves. (those who are not comfortable sitting on the floor sit on chairs). This is the only time of the year that we actually sit on the floor during a service—and I welcome this. The synagogue is transformed from a place of uprightness and formality to a place of quiet inwardness. We create a sanctuary of silence.

Out of the darkness, someone begins to chant the mournful yet exquisitely poignant melody of Eicha, the text of Lamentations. Heads bowed, we read the words by the light of our candles. Curiously, the Hebrew word that begins the lament, Eicha—echoes the word Ayecha from the Garden of Eden story linking these stories. Ayecha is translated as “where are YOU”? When God cries out, ayecha, God is confronting Adam and Eve, who are hiding from God--shirking their responsibility. In the book of Lamentations, the term Eicha—translates to a mournful complaint “HOW-How is it possible?” When I read the word Eicha in light of Ayecha, I hear: HOW, How could YOU let this happen to my precious garden, my earth, my creatures, my peoples?

The text is shocking, appalling. But the language is so rich and the imagery so disturbing that I am deeply moved. I sit with one verse and let it wash over me; then I am pulled to another and I sink into that one. It is strangely immediate.

My eyes are worn out from weeping; my stomach is churning.

My insides are poured on the ground . . .,

because children and babies are fainting in the city streets.They say to their mothers, “Where are grain and wine?”

while fainting like the wounded in the city streets,

while their lives are draining away at their own mothers’ breasts.

2:11-12Your hurt is as vast as the sea. Who can heal you?

2:13

Children ask for bread, beg for it—but there is no bread.

Those who once ate gourmet food now tremble in the streets.

Those who wore the finest purple clothes now cling to piles of garbage.

4.4-5The Lord let loose in fury; poured out fierce anger.

The Lord started a fire in Zion; it licked up the foundations.The earth’s rulers didn’t believe it—neither did any who inhabit the world.

4.11-12We drink our own water—but for a price; we gather our own wood—but pay for it.

. . . we are worn out, but have no rest.

5:4-5

As I read and listen, I reflect on the fires that have devasted so much of the forests, creatures and homes of the western U.S. and the smoke-tinged crops in California—now inedible. I think of the new normal—the unaffordable price of wood. I think of climate refugees, including those here in America, who have been flooded or smoked out of their homes. I think of those who endure year after year of drought, wondering where their next meal will come from, wondering how they will feed their children. I think of the earth’s rulers and so many others who “didn’t believe it”—who didn’t believe this could happen to us.

The ritual of Tisha B’Av makes the suffering more bearable. It encourages us to face the pain—not run from it. Through our participation in this ritual, we create a container that holds the community—a container that gives us the space to weep alone together in our grief. I am grateful that my tradition is not afraid to acknowledge this extraordinarily difficult truth about the nature of humanity and the nature of life, and this gives me some peace. And my sometimes-tortured soul is soothed.

** Rabbi Ellen Bernstein founded Shomrei Adamah, the first national Jewish environmental organization (1988) and her most recent book is The Promise of the Land: A Passover Haggadah. She was born on Tisha B’Av.

Comments powered by CComment