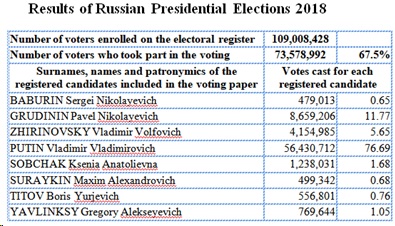

In Russia’s presidential election in March, Vladimir Putin secured an impressive 76% of the vote – in line with a long history of broad public approval of his regime. But, with Russians becoming more worried about their futures than at any point since Putin first came to power, his popular support is slipping away.

In Russia’s presidential election in March, Vladimir Putin secured an impressive 76% of the vote – in line with a long history of broad public approval of his regime. But, with Russians becoming more worried about their futures than at any point since Putin first came to power, his popular support is slipping away.

Moscow, Sept. 14.– From controlling the media to stoking nationalism, Russian President Vladimir Putin has always known how to keep his approval ratings high. But Russians’ lives are not getting any better, especially after the latest round of Western economic sanctions – and Putin’s declining approval rating shows it.

In April, the ruble was tumbling, owing partly to the sanctions imposed in response to the Kremlin’s alleged poisoning of the former Russian double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter on British soil. Then, in June, just as the Russia-hosted World Cup was getting underway, the government proposed increasing the retirement age from 60 to 65 for men and from 55 to 63 for women, prompting an immediate public backlash. The result was a sharp 15-point decline in the approval rating of the government overall – the largest decline of Putin’s 18-year rule.

Moreover, trust in Putin himself dipped to 48%, from about 60%. To put that in perspective, even at the beginning of Putin’s third term in 2012 – when there were mass protests over his return to the presidency after his stint as prime minister – around 60% of Russians said that they trusted him.

At that time, Putin raised his approval rating by establishing himself as Russia’s defender. When the United States, under President Barack Obama, showed itself to be unwilling to enforce its “red line” in Syria – the use of chemical weapons by President Bashar al-Assad – the Kremlin jumped in, establishing Russia as a sinister guarantor of Assad’s disarmament.

To reinforce his domestic standing further by signaling that Russia does not bend to America’s will, Putin granted asylum to National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden. Within Russia, Putin ensured that new bridges and roads were built, infrastructure was upgraded, and public spaces were renewed, with parks, fountains, and cafes.

Though none of this helped Russians economically, much less expanded their freedoms, it established Putin as a champion of “Great Russia.” After Russia invaded Ukraine and annexed Crimea in March 2014 – unapologetically defying the West – his approval rating reached a dizzyingly high 87%.

In March, Putin won the presidential election handily, securing his fourth term as president with 76% of the vote, owing partly to the absence of other viable candidates. Immediately after the election, his approval rating stood at 82%.

But the World Cup that began soon after took a toll. By bringing over 700,000 international visitors, the tournament changed Russians’ perception of what matters – and of their leader. An ungracious host, Putin stood under an umbrella during the final post-match ceremony, while the presidents of Croatia and France got soaked by the pouring rain.

Meanwhile, the Russian people impressed the world with their happy hospitality. The bar owners, train conductors, and English-speaking volunteers welcomed visitors warmly. Russians realized that they didn’t need to win at all costs; they could be great without the Kremlin’s militaristic say-so.

Then the pension reform was announced, spurring a string of protests that drove Putin to pledge to soften the measure, while asking for Russians’ understanding. Yet, as of September 3, 53% of the population said that they were ready to protest further. And on September 9, while local government elections took place, tens of thousands of Russians joined protests organized by the anti-corruption lawyer and opposition leader Alexei Navalny, defying the prohibition of “political agitation” on election days.

Navalny himself couldn’t attend the event, after being arrested for a previous unsanctioned demonstration. But that didn’t stop at least 2,500 protesters from showing up on Moscow’s Pushkin Square, where they stood up to merciless police, waving signs emblazoned with slogans like “No Way” (a play on Putin’s name: “put” means “way” in Russian) and “Putin, it’s time to retire” (he is 65).

Protesters included many young people, who are angry not just about the pension reform, which will not affect them for a long time, but about the Putin regime’s wider failings. Many believe that even if Putin has restored Russia’s status as a “great power,” that does not compensate for rampant corruption and a lack of opportunities at home. Young people view the regime as outdated, and Putin himself as an obstacle to the changes – such as increased investment in social programs – needed to raise living standards.

But it is not just young people who are souring on Putin. Russian businesspeople are frustrated by the effects of sanctions and angry about planned tax increases. Like young Russians, entrepreneurs are questioning whether Putin’s assertive foreign policy of militant nationalism, which won him so much domestic support in the past, is worth the price, including the actual cost of Russia’s military activities and the impact of Russia’s increasing economic and political isolation from the West.

Putin surely knows that his position is shaky. That is why police meted out such rough treatment to protesters, arresting them by the hundreds. The Kremlin fears not only more rallies, but also intensifying opposition from businesspeople, some of whom rank among Russia’s powerful elites. Regional authorities could also begin to sabotage the Kremlin’s decisions.

Putin’s image as a steward of Russia’s greatness and a symbol of hope is slipping away, and his tried-and-true tactic for renewing his popularity – say, annexing territory from a neighboring country or intervening in a civil war – is not a practical long-term strategy. Unless Putin makes real changes within Russia, his approval rating will continue to slide, increasing the chances that one way or another, he will finally leave the presidency when his current term expires in 2024, if not before.

* Nina L. Khrushcheva, the author of Imagining Nabokov: Russia Between Art and Politics and The Lost Khrushchev: A Journey into the Gulag of the Russian Mind, is Professor of International Affairs at The New School and a senior fellow at the World Policy Institute.

* Nina L. Khrushcheva, the author of Imagining Nabokov: Russia Between Art and Politics and The Lost Khrushchev: A Journey into the Gulag of the Russian Mind, is Professor of International Affairs at The New School and a senior fellow at the World Policy Institute.

Comments powered by CComment