From the other side of the Wall

- Barbara E. Joe

-

Topic Author

- Offline

- New Member

-

- Posts: 16

- Thanks: 1

From the other side of the Wall

01 Apr 2019 18:17

My Recent Experiences in Honduras

In February, 2019, as I got off the bus in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, after returning from the south, a man waiting at the bus stop shouted out for all to hear, “Señora, whatever are you doing traveling around this country all by yourself? Where is your husband?” I said that he had died [indeed, my ex-husband had died]. “Where are your children?” I said they were in the US. “What a travesty,” he muttered, “very sad.”

Indeed, he has not been my only critic. My own adult children question why, as a woman of a certain age, I still return every February to Honduras, the country where, already in my 60’s, I served from 2000 to 2003 as a Peace Corps health volunteer? The Corps subsequently left that country after 50 years because of a clear and present danger. Yet, I have continued to return annually on my own as a volunteer, bringing medical and other supplies and serving as a medical interpreter and helper for foreign medical brigades, traveling around by taxi and ordinary buses within cities and all over the country, transporting considerable baggage, like wheelchairs, walkers, crutches, and medical supplies. Does that mean there is no real risk and that the migrants, whom Donald Trump has characterized as an ”invasion,” really have nothing to fear by staying home? He has ordered a cut off of aid to Honduras and other countries in retaliation and has threatened to close the border.

On the contrary, I am taking a daily risk. Almost every Honduran I’ve spoken with this year and over the last 19 years, tells personal stories of being robbed or threatened at gunpoint, having had a car highjacked, or being subjected to a home invasion. Cars are rarely insured as it’s too costly; so a stolen car is just gone. These threats include people of all economic classes, from the wealthy with their compounds rimmed by high walls and razor wire with armed guards stationed outside, to cab drivers, to humble families using outdoor latrines and kerosene lamps. Neighbors may get together to block off streets and hire a 24-hour guard among them. Robberies, threats, rapes, machete and firearm injuries, and even murders are everyday occurrences. Honduran daily newspapers display lurid headlines and photos of dead bodies seeping with red blood and TV news does the same.

In my part-time work as a Spanish interpreter back home in Washington, DC, I’ve heard credible tales of threats of rape and murder from Hondurans and other Central American asylum applicants. I have seen their scars. So, I do consider the danger real and try to avoid risky areas when traveling there, though that’s often impossible.

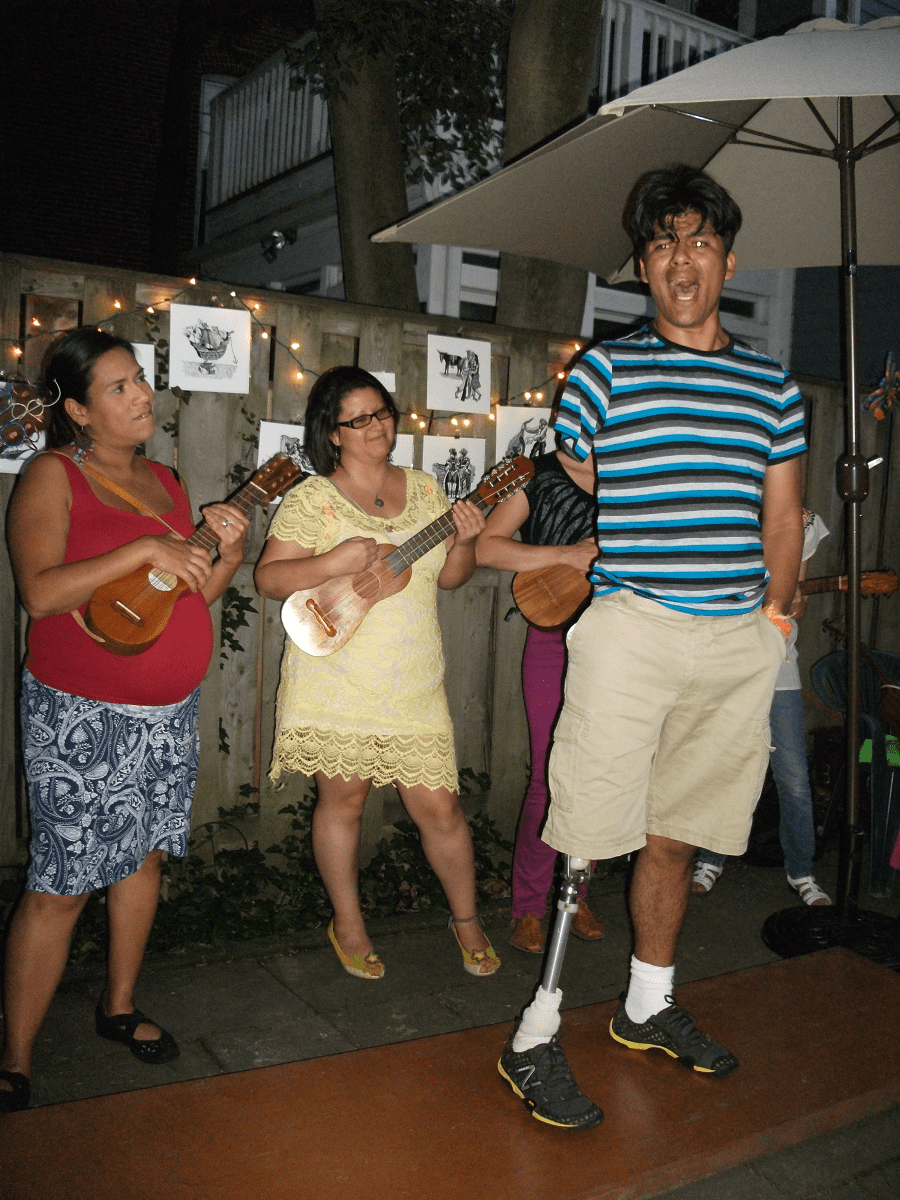

When I lived in Honduras for 3½ years while in the Peace Corps, was I ever personally threatened, harmed, or robbed? Let me count the ways! Despite taking constant precautions, I was subjected to my fair share of robberies and even minor physical harm, such as when a guy snatched a cap off my head, or when another snuck up behind me to violently yank off my pierced gold earrings, or when a purse snatcher pulled me down to the ground, cracking my front tooth and bruising my ribs when I fell, as bystanders gave chase. At my residence, when I used an outdoor latrine or bathed outside by pouring pila water over my head and body, I always padlocked my bedroom door, as my transistor radio and pocket knife had disappeared during a brief absence. I kept an eye on clothes hanging out to dry, lest they be snatched off the clothesline. For hotel maids or food servers, I always put a tip right into their hand, never leaving it in the room or on the table. When I went downstairs briefly from a low-budget hotel in the capital (all we could afford on our Peace Corps stipend), several belongings disappeared, including my Peace Corps ID, which miraculously was turned into our headquarters by someone who’d found it discarded in the gutter. Once I woke up screaming as from a nightmare when a robber dropped down from a hole made in the tile roof and appeared suddenly in my bedroom while I was sleeping. I know a Honduran nurse who suffered a cut on her neck narrowly missing the carotid artery during a daylight purse snatching in La Esperanza, a high-altitude town considered relatively safe. Dogs remain outside as guards, not pets. Crimes are rarely reported to the police, considered ineffective or actually in cahoots with criminals. Crime is a constant threat and always having to be on guard exacts an emotional toll. As a Peace Corps volunteer, I’ve helped returnees readjust to life back home and helped obtain protheses for amputees injured jumping off Mexican trains. “I just wanted to help my family, build a house for my mother,” one tearful amputee told me.

Many cab drivers told me about having lived for a few years in Houston or New York City until being deported. Deportees can be seen returning daily at major airports. However, that does not dampen the almost universal aspirations of folks who dream of a fairytale life in the USA, where they will not only be safe, but earning big bucks instead of struggling just to survive by picking coffee by hand, chopping down old corn or sugarcane stalks with a machete, or plowing fields with oxen. Relatives working in the US tell about earning $10, $15, or even $20 per hour, more than they might earn in a single day or even a whole week. Wouldn’t it be worth taking a risk, especially if you or your family are being threatened and perhaps going hungry? Hurricanes, floods, earthquakes, volcano eruptions, and droughts may provide the final impetus in countries where agriculture is still the mainstay. For young people, a stint in the USA is almost a rite of passage. While the median age in the US is now about 38, in Honduras, it is only 23. “What are your future plans?” I’ve often asked a teenager; “Going up to ‘Yuma,’ [one of several US nicknames]” is a frequent reply.

I’ve also traveled in Guatemala and El Salvador, hearing similar tales, including of murders when extortion requests were not met. Theft, rape, and murder seem imbedded in the culture, so it’s not surprising to see armed guards in grocery stores, banks, Western Union offices, hospitals, pharmacies, and even ice cream parlors. Quite obviously, if these dangers are universal in Honduras and other triangle countries, the United States cannot offer refuge to the millions being affected. The reasons for the continued risks are many: lack of opportunity, scarcity, rampant inequality, police and political corruption, and other factors that the US can affect only indirectly. The greatest benefits for the citizens of Honduras and neighboring countries may come from the remittances sent by their relatives working legally or not in the United States.

Several rumors were making the rounds among would-be migrants in Honduras just now. One is that lots of work is available, which is partially true. Traveling with a child is thought to be safer and to help someone get out of detention and even obtain asylum (why so many main breadwinner fathers are traveling with one small child). There is also a fear that the opportunity may soon be closing because of constant threats from the U.S. president. Some would-be migrants say they consider Mexico to be a good-enough second choice destination and still an improvement over staying in Honduras.

A number of folks repeated the rumor that the Honduran “caravans” had been deliberately organized by Manuel Zelaya, former president and foe of the current president, undertaken simply to embarrass him. Traveling by caravan not only eliminates or reduces payment to a coyote, but is considered safer and provides information (both correct and suspect), as well as camaraderie, support, and a sense of shared purpose. Not have only Central American travelers banded together, but Cubans seeking U,S. asylum have also joined the mix. (Recently deported from Mexico were 66 Cubans, the only migrants Mexico seems to be deporting.) Much better to confront Mexican authorities and US border agents as part of a crowd. Many hope to join family members already in the U.S. As the numbers grow, Trump’s warning of an “invasion” seems almost to be coming true.

Yet others pointed out that Colombia, with less capacity than the United States, is accepting proportionately greater numbers of Venezuelans with “no wall, no papers, no nothing.”

“A wall cannot keep us out,” a taxi driver told me. “Gringos need our labor and we need their dollars. Even Mr. Trump employs us. We are all citizens of the Americas, after all. A wall, you can always go over, under, or around it.”

Another man, deported after a drunk driving conviction and having no license, said, “It was a lot harder than I’d expected, both the journey and actually living there. But I’m not sorry. I earned money; I learned a lot.” He said he returned a wiser man to his family in Honduras, but also leaving behind a US-born child.

Most Hondurans dismissed Trump’s threats to halt aid. “So what? American aid just helps the government and people who are already rich, not us, not migrants.”

A friend working with the Honduran Red Cross told me that he and his colleagues try to relocate deportees who express a genuine fear of returning to their original homes, often referring them to local chapters for help. Honduras is not a huge country; it has about 9 million citizens and covers a territory a little larger than Tennessee. But it is sometimes possible to relocate deportees away from the gangs, rivals, and former domestic partners who have threatened them.

Many Hondurans grudgingly opine that their president’s controversial strong-arm tactics have had some dampening effect on crime.

What else can be done? It would be great if the Peace Corps could return, as we always worked to empower people to join together to improve their own situation. However, the danger to volunteers is still too great. Besides, the Trump administration has proposed cutting the Peace Corps budget now for the third year in a row. This U.S. administration is also not big on regional trade agreements. So far, the current Honduran President, Juan Orlando Hernández, is trying to stay on the good side of Donald Trump. President Hernández, popularly referred to by his initials of JOH, was recently seen dining in a DC restaurant along with his aides.

So, Hondurans and other Central Americans will continue to vote with their feet, Trump or not, wall or no wall.

In February, 2019, as I got off the bus in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, after returning from the south, a man waiting at the bus stop shouted out for all to hear, “Señora, whatever are you doing traveling around this country all by yourself? Where is your husband?” I said that he had died [indeed, my ex-husband had died]. “Where are your children?” I said they were in the US. “What a travesty,” he muttered, “very sad.”

Indeed, he has not been my only critic. My own adult children question why, as a woman of a certain age, I still return every February to Honduras, the country where, already in my 60’s, I served from 2000 to 2003 as a Peace Corps health volunteer? The Corps subsequently left that country after 50 years because of a clear and present danger. Yet, I have continued to return annually on my own as a volunteer, bringing medical and other supplies and serving as a medical interpreter and helper for foreign medical brigades, traveling around by taxi and ordinary buses within cities and all over the country, transporting considerable baggage, like wheelchairs, walkers, crutches, and medical supplies. Does that mean there is no real risk and that the migrants, whom Donald Trump has characterized as an ”invasion,” really have nothing to fear by staying home? He has ordered a cut off of aid to Honduras and other countries in retaliation and has threatened to close the border.

On the contrary, I am taking a daily risk. Almost every Honduran I’ve spoken with this year and over the last 19 years, tells personal stories of being robbed or threatened at gunpoint, having had a car highjacked, or being subjected to a home invasion. Cars are rarely insured as it’s too costly; so a stolen car is just gone. These threats include people of all economic classes, from the wealthy with their compounds rimmed by high walls and razor wire with armed guards stationed outside, to cab drivers, to humble families using outdoor latrines and kerosene lamps. Neighbors may get together to block off streets and hire a 24-hour guard among them. Robberies, threats, rapes, machete and firearm injuries, and even murders are everyday occurrences. Honduran daily newspapers display lurid headlines and photos of dead bodies seeping with red blood and TV news does the same.

In my part-time work as a Spanish interpreter back home in Washington, DC, I’ve heard credible tales of threats of rape and murder from Hondurans and other Central American asylum applicants. I have seen their scars. So, I do consider the danger real and try to avoid risky areas when traveling there, though that’s often impossible.

When I lived in Honduras for 3½ years while in the Peace Corps, was I ever personally threatened, harmed, or robbed? Let me count the ways! Despite taking constant precautions, I was subjected to my fair share of robberies and even minor physical harm, such as when a guy snatched a cap off my head, or when another snuck up behind me to violently yank off my pierced gold earrings, or when a purse snatcher pulled me down to the ground, cracking my front tooth and bruising my ribs when I fell, as bystanders gave chase. At my residence, when I used an outdoor latrine or bathed outside by pouring pila water over my head and body, I always padlocked my bedroom door, as my transistor radio and pocket knife had disappeared during a brief absence. I kept an eye on clothes hanging out to dry, lest they be snatched off the clothesline. For hotel maids or food servers, I always put a tip right into their hand, never leaving it in the room or on the table. When I went downstairs briefly from a low-budget hotel in the capital (all we could afford on our Peace Corps stipend), several belongings disappeared, including my Peace Corps ID, which miraculously was turned into our headquarters by someone who’d found it discarded in the gutter. Once I woke up screaming as from a nightmare when a robber dropped down from a hole made in the tile roof and appeared suddenly in my bedroom while I was sleeping. I know a Honduran nurse who suffered a cut on her neck narrowly missing the carotid artery during a daylight purse snatching in La Esperanza, a high-altitude town considered relatively safe. Dogs remain outside as guards, not pets. Crimes are rarely reported to the police, considered ineffective or actually in cahoots with criminals. Crime is a constant threat and always having to be on guard exacts an emotional toll. As a Peace Corps volunteer, I’ve helped returnees readjust to life back home and helped obtain protheses for amputees injured jumping off Mexican trains. “I just wanted to help my family, build a house for my mother,” one tearful amputee told me.

Many cab drivers told me about having lived for a few years in Houston or New York City until being deported. Deportees can be seen returning daily at major airports. However, that does not dampen the almost universal aspirations of folks who dream of a fairytale life in the USA, where they will not only be safe, but earning big bucks instead of struggling just to survive by picking coffee by hand, chopping down old corn or sugarcane stalks with a machete, or plowing fields with oxen. Relatives working in the US tell about earning $10, $15, or even $20 per hour, more than they might earn in a single day or even a whole week. Wouldn’t it be worth taking a risk, especially if you or your family are being threatened and perhaps going hungry? Hurricanes, floods, earthquakes, volcano eruptions, and droughts may provide the final impetus in countries where agriculture is still the mainstay. For young people, a stint in the USA is almost a rite of passage. While the median age in the US is now about 38, in Honduras, it is only 23. “What are your future plans?” I’ve often asked a teenager; “Going up to ‘Yuma,’ [one of several US nicknames]” is a frequent reply.

I’ve also traveled in Guatemala and El Salvador, hearing similar tales, including of murders when extortion requests were not met. Theft, rape, and murder seem imbedded in the culture, so it’s not surprising to see armed guards in grocery stores, banks, Western Union offices, hospitals, pharmacies, and even ice cream parlors. Quite obviously, if these dangers are universal in Honduras and other triangle countries, the United States cannot offer refuge to the millions being affected. The reasons for the continued risks are many: lack of opportunity, scarcity, rampant inequality, police and political corruption, and other factors that the US can affect only indirectly. The greatest benefits for the citizens of Honduras and neighboring countries may come from the remittances sent by their relatives working legally or not in the United States.

Several rumors were making the rounds among would-be migrants in Honduras just now. One is that lots of work is available, which is partially true. Traveling with a child is thought to be safer and to help someone get out of detention and even obtain asylum (why so many main breadwinner fathers are traveling with one small child). There is also a fear that the opportunity may soon be closing because of constant threats from the U.S. president. Some would-be migrants say they consider Mexico to be a good-enough second choice destination and still an improvement over staying in Honduras.

A number of folks repeated the rumor that the Honduran “caravans” had been deliberately organized by Manuel Zelaya, former president and foe of the current president, undertaken simply to embarrass him. Traveling by caravan not only eliminates or reduces payment to a coyote, but is considered safer and provides information (both correct and suspect), as well as camaraderie, support, and a sense of shared purpose. Not have only Central American travelers banded together, but Cubans seeking U,S. asylum have also joined the mix. (Recently deported from Mexico were 66 Cubans, the only migrants Mexico seems to be deporting.) Much better to confront Mexican authorities and US border agents as part of a crowd. Many hope to join family members already in the U.S. As the numbers grow, Trump’s warning of an “invasion” seems almost to be coming true.

Yet others pointed out that Colombia, with less capacity than the United States, is accepting proportionately greater numbers of Venezuelans with “no wall, no papers, no nothing.”

“A wall cannot keep us out,” a taxi driver told me. “Gringos need our labor and we need their dollars. Even Mr. Trump employs us. We are all citizens of the Americas, after all. A wall, you can always go over, under, or around it.”

Another man, deported after a drunk driving conviction and having no license, said, “It was a lot harder than I’d expected, both the journey and actually living there. But I’m not sorry. I earned money; I learned a lot.” He said he returned a wiser man to his family in Honduras, but also leaving behind a US-born child.

Most Hondurans dismissed Trump’s threats to halt aid. “So what? American aid just helps the government and people who are already rich, not us, not migrants.”

A friend working with the Honduran Red Cross told me that he and his colleagues try to relocate deportees who express a genuine fear of returning to their original homes, often referring them to local chapters for help. Honduras is not a huge country; it has about 9 million citizens and covers a territory a little larger than Tennessee. But it is sometimes possible to relocate deportees away from the gangs, rivals, and former domestic partners who have threatened them.

Many Hondurans grudgingly opine that their president’s controversial strong-arm tactics have had some dampening effect on crime.

What else can be done? It would be great if the Peace Corps could return, as we always worked to empower people to join together to improve their own situation. However, the danger to volunteers is still too great. Besides, the Trump administration has proposed cutting the Peace Corps budget now for the third year in a row. This U.S. administration is also not big on regional trade agreements. So far, the current Honduran President, Juan Orlando Hernández, is trying to stay on the good side of Donald Trump. President Hernández, popularly referred to by his initials of JOH, was recently seen dining in a DC restaurant along with his aides.

So, Hondurans and other Central Americans will continue to vote with their feet, Trump or not, wall or no wall.

Reply to Barbara E. Joe

Moderators: Miguel Saludes, Abelardo Pérez García, Oílda del Castillo, Ricardo Puerta, Antonio Llaca, Efraín Infante, Pedro S. Campos, Héctor Caraballo

Time to create page: 0.193 seconds